NYC released its grading policy this week. Within this policy is a great amount of flexibility for teachers to shape how grades impact learners. Mastery Collaborative Mentor from active member school NYC iSchool, Kristen Brown takes on the important questions: Are my grades are fair, accurate, and giving my students the feedback I think they need to really improve? Are my assessments and the way I evaluate students perpetuating an unjust system that disproportionately fails more students of color than white students?

She tells about her experience reading Joe Feldman’s book 2019 book Grading for Equity and how it’s furthered her thinking about assessing students in a fair and non-punitive manner.

What are my grades really telling my students?

Grading for Equity, by Joe Feldman

I have been trying for the last few years to think about how we can change our education system so it works for everyone. I have attended countless workshops and have read every book I could find about how I could change my teaching practices, my curriculum, and my classroom culture to be more culturally responsive, but I still felt that some of my grading practices and grading calculations were perpetuating inequity.

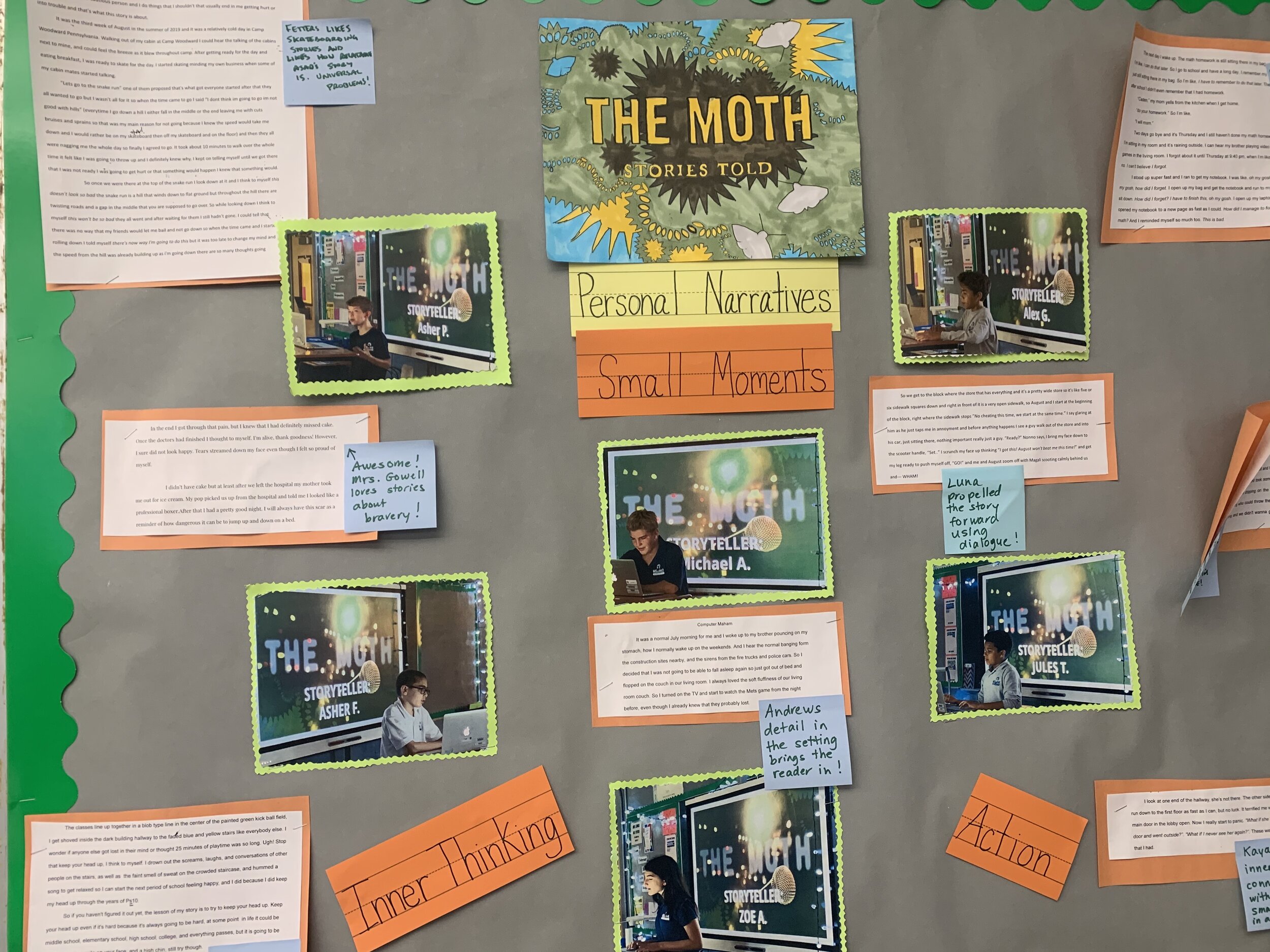

A few months ago, I walked into the teacher’s lounge and saw a book called Grading for Equity by Joe Feldman. It is a resounding endorsement of mastery based grading and it has some of the clearest reasoning behind why we must only grade students on what they master in our classrooms and not on who they are or on factors they cannot control. The book reinforced for me that I am a white, upper middle class woman and everything I do in the classroom is filtered through that racial lens, including the way I grade.

There is a lot at stake in grading. Grades decide so much about students: who gets to take Advanced Placement courses or who receives honors distinctions. Students begin to identify with the labels we give them through grades. Feldman makes the case that we think about grades as objective because there’s a strict formula and calculation, but in fact they are steeped in our own biases and how we view student work and behavior in our classrooms. Below are two examples of how cultural bias creeps into common grading practices.

“I am a white, upper middle class woman and everything I do in the classroom is filtered through that racial lens, including the way I grade. ”

Cultural bias in grading: 2 examples

Teachers often use participation grades as a means of classroom management, but what do we really mean when we say participation? What lens are we using when we evaluate participation? I grew up in a white middle class family in a white middle class suburb, a completely different reality than most of my students. As a student I thought of participation as quietly listening to the teacher speak and then raising my hand if I had a question or comment for the teacher. As a teacher, if one of my students likes to gesticulate or jump in when I’m speaking because they’re so excited about the topic or they have just made a great connection to what I just said, I judge this action through my white cultural lens. I might see his excitement as disruptive, worthy of losing points, rather than as a sign of active participation.

When I deduct points, or correct this cultural behavior, will that admonishment embarrass this student? What will he internalize about this interaction? The message this simple act of grading sends is that I, and years of teachers prior, don’t value his opinion, his way of being, or, worse, see him as deficient. Will that student want to participate again and share his brilliant connection or his joy of the subject? Probably not.

Another common way of measuring participation is grading participation in a classroom discussion. But what does that do to the student who is excited about the topic and actively listening, but is painfully shy or embarrassed by the fact that English is not her first language? Will she be able to continue to actively listen to the discussion? Zaretta Hammond tells us that in moments of cultural misunderstanding, students’ flight or flight response is triggered. Will evaluating the student’s silence trigger this response and leave her unable to focus enough to deeply think about the topic being discussed? Has grading this discussion through my cultural lens encouraged the student or penalized her?

These grades are not objective. I can’t help but put my own implicit biases and my own cultural lens into how I interpret the classroom behavior, which informs my participation grade. If I really stepped back and looked at the last two scenarios, I might realize that those two students were actively participating, just not in the way I would have. Grading behavior is affected by my own cultural biases, and ultimately unfair for many of our students.

“In order for our grades to be accurate, bias-resistant, and support a growth mindset, we need to stop grading soft skills as part of our final grade calculation.”

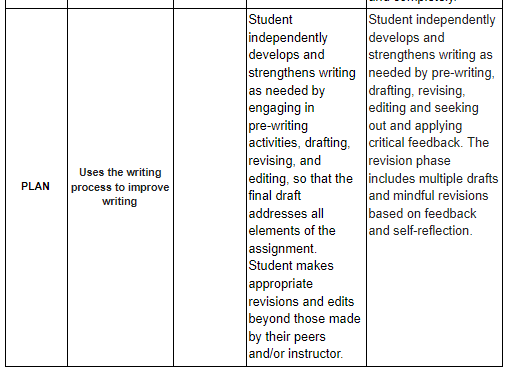

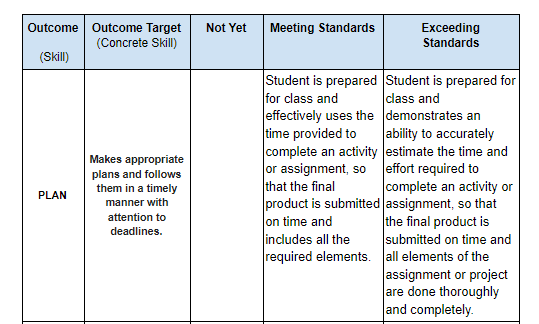

None of this means “soft skills” are not important, or that they don’t impact a student’s academic performance. They absolutely do, but when we assign them a point value we are devaluing the ideals of growth and mastery. Feldman argues that we should record soft skills and communicate clear expectations for what students need to do to be successful in our classrooms, but this should only be a tool for us to have a larger conversation about what students need to do to master the content and the skills that we judge important for the 21st century. He rightly argues that in order for our grades to be accurate, bias-resistant, and support a growth mindset, we need to stop grading soft skills as part of our final grade calculation. If we can do this, maybe our classrooms will move one step closer toward an education system that truly works for all students.

Thanks, Kristen, for sharing your thoughts. We love Joe Feldman’s book and its approachable explanation of these issues we care deeply about.

Kristen teaches high school biology and health at the NYC iSchool and she is a MƒA Master Teacher with 13 years of experience in NYC public schools. She has practiced mastery-based grading for ten years and recently started to co-facilitate the mastery team meetings at her school with the goal of rethinking what practices students need to master to be successful in our current world. In addition to mastery-based teaching, her professional passions include U.S. farm policy, gardening, U.S. drug policy, reproductive health, social justice, and anti-racist teaching. Kristen lives in East Harlem with her husband, two daughters, and their cat, Oliver Twist.